Whether you have arrived here with the intent of learning the game of bridge, or got lost on your search regarding the physical bridges, welcome! If you’ve arrived here with the explicit intent of learning bridge – you’re in the right place. If you have not – maybe my intro will catch your interest.

I wanted to make this series an ultimate guide to the bridge basics. One such that once you complete it, you’ll not only be able to play bridge, but also start seeing and appreciating the intricacies of the game that lay ahead. Now, without further ado, let’s get into it!

IN THIS LESSON YOU’LL LEARN the basics of bridge, i.e. its rules. You’ll learn about the general setup and the structure of the deal. I’ll explain the concepts like: trump suit, contract, trick, dealer, declarer, dummy or bid.

Bridge is a card game played by millions of people globally. We meet up in local clubs or play online. It’s a great social pastime, mixing intellectual challenge with moments of rest perfect for some chit chat.

You need four players for a game of contract bridge. You’ll play in two teams of two. If you sit at a square table with three of your friends, each on one side, your partner will be the person sitting opposite of you, with your opponents sitting on your sides.

Pro tip: The players are usually called and referred to by the cardinal directions: North, South, East, West or N, S, E, W in short. Player N is partnered up with player S and player E with player W. They are seated in accordance with the map, as shown in the picture on the side.

We play with a standard deck of 52 cards, ordered like in the picture on the side. What I mean by that is that an ace is a stronger card than a king, a king is stronger than a queen, a jack stronger than ten, etc.

At the beginning of the game (or a deal, I’ll use these interchangeably) the players are each dealt 13 cards. They keep them secret. The dealer will start the game. The dealer in the next deal will be the person sitting to the left of the current dealer.

The game consists of two phases: bidding and card play (or simply, play). And now things will start getting a little complicated, especially if you’re new to card games. I tried to organize my explanation in a way easiest to understand, but there are still some concepts I have to introduce before explaining them in full later. Just bear with me. I’ll present some partial examples in relevant sections of this post, and at the end of this lesson, I’ll show you a full sample deal.

The purpose of the bidding is to come up with a contract – a bet where one of the teams promises to win a certain amount of tricks, and dictates if and which suit will be the trump suit. An example of the contract would be: We (N and S) will take 9 tricks and the trump suit is clubs (for further reference: we’d call such a contract 3♣). The goal of the team that won the bidding (attackers) is to meet the contract (i.e. take at least as many tricks as the contract states), the other team (defenders) will try to stop them from doing so.

Now, I know a lot has happened very fast in the previous sentence, in the spirit of this good ol’ owl tutorial:

So let me explain it in detail. I’ll start from the end, however – let’s talk about…

Card play

As mentioned before, the play phase picks up where bidding left off. We have a contract – one of the teams declared they will take a number of tricks in this deal. So how do you take tricks?

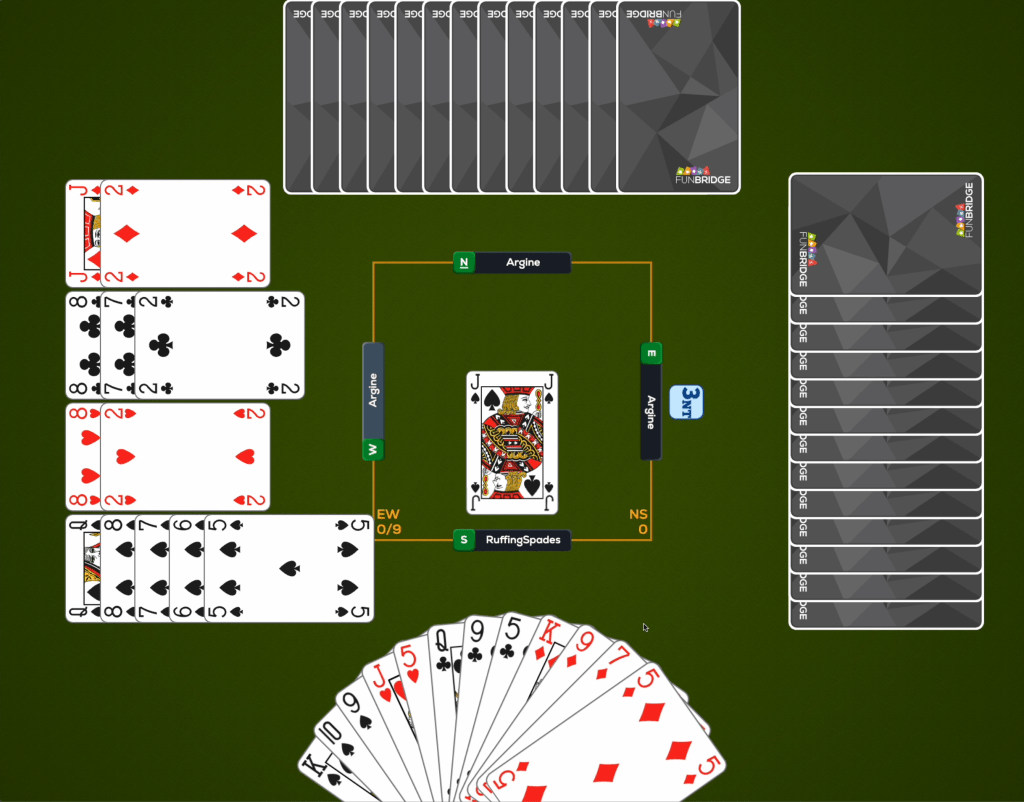

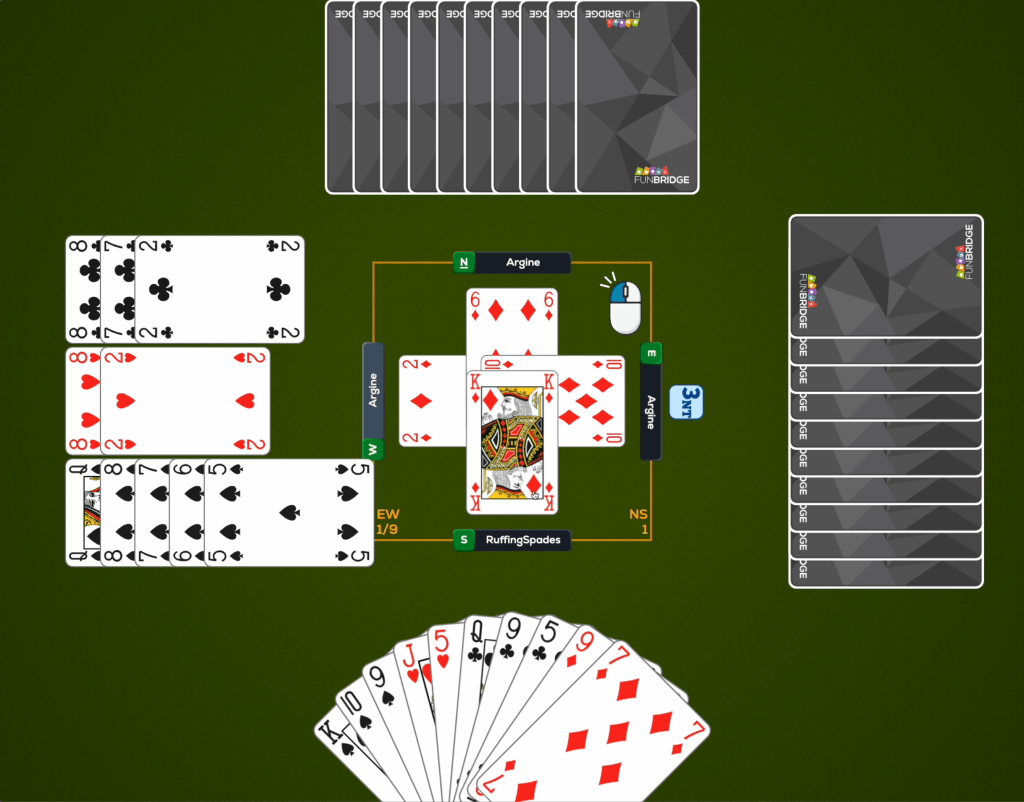

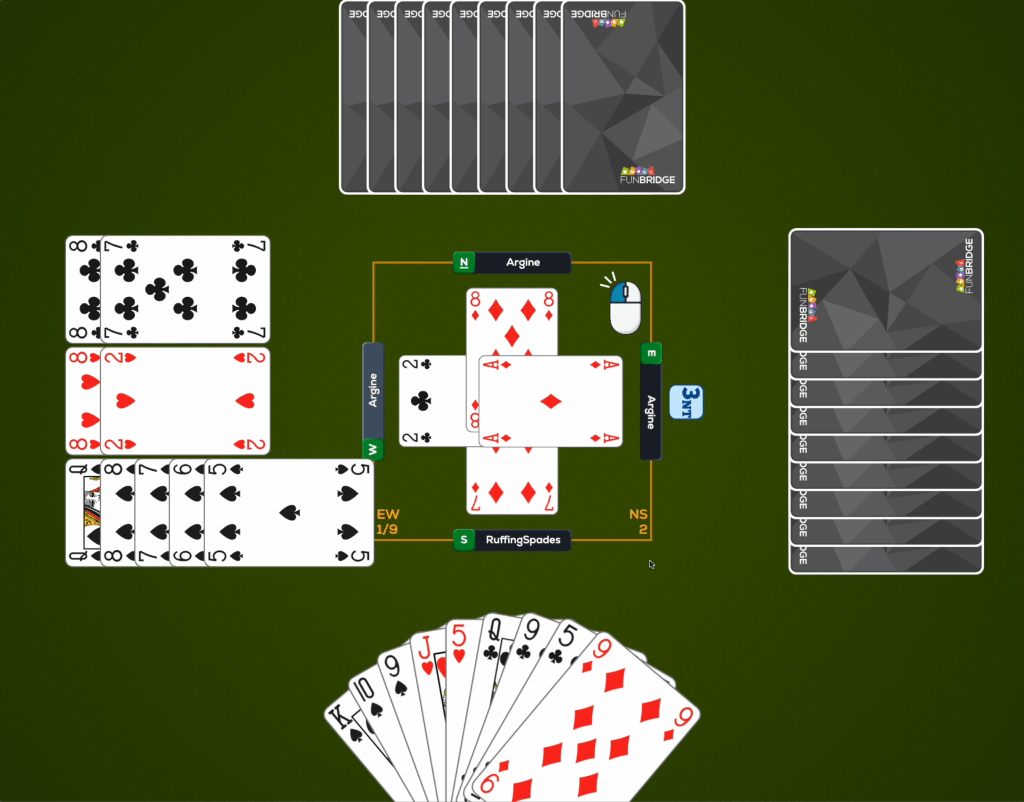

The play starts with the declarer – the winner of the bidding (I’ll elaborate on it later) – opening the first trick. From then on, every next trick is started by the player who won the previous one. You open a trick by placing one of your cards on the table, then the person to their left puts one of theirs, then the next person and the next. The person with the highest card out of the four wins the trick.

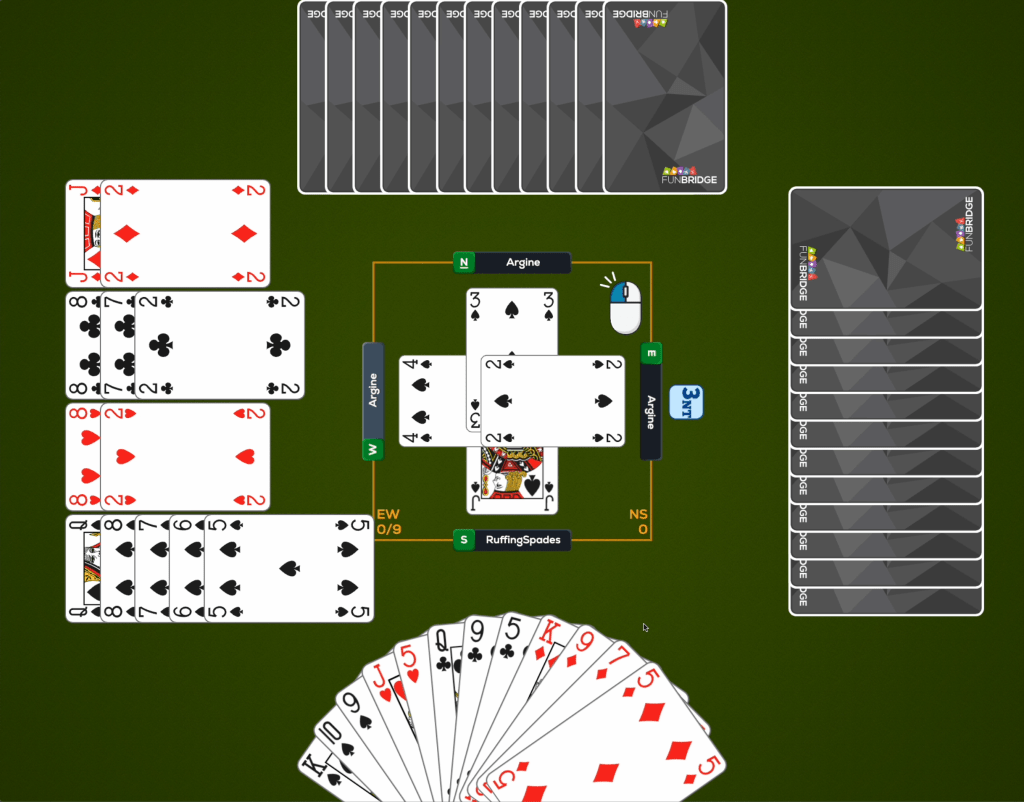

Now, there are some extra rules here. First and foremost, when placing your card to an already open trick you must match the suit of the opening card if you can. If you don’t have any cards matching the suit, you can play any card you want. For example, the player N put forth a Q♥, that means every player has to play a heart in this trick, unless they don’t have one. If you are W and are all out of hearts, you can put any card you want.

And how do we decide who takes the trick? The highest card of the trick suit takes the trick, unless a card of the trump suit was played – then the highest trump takes the trick. From this we can observe that the ace of the trump suit will always take a trick. And also, it’s possible that a non-trump ace won’t. Don’t worry if it’s a little confusing – near the end of this section I’ll go through a couple of examples.

The players keep playing tricks until they’re out of cards in their hand. In total, in each deal there will be 13 tricks played (52 cards in a deck are divided between 4 players, so each player has 13. Every trick takes a card from each player.)

But that’s not all. There is something special about bridge – and that is that in every deal there is one person at the table that gets to lean back and relax the moment bidding concludes – the dummy. (Remember when I mentioned that there are times to lay back and relax during the game of bridge?).

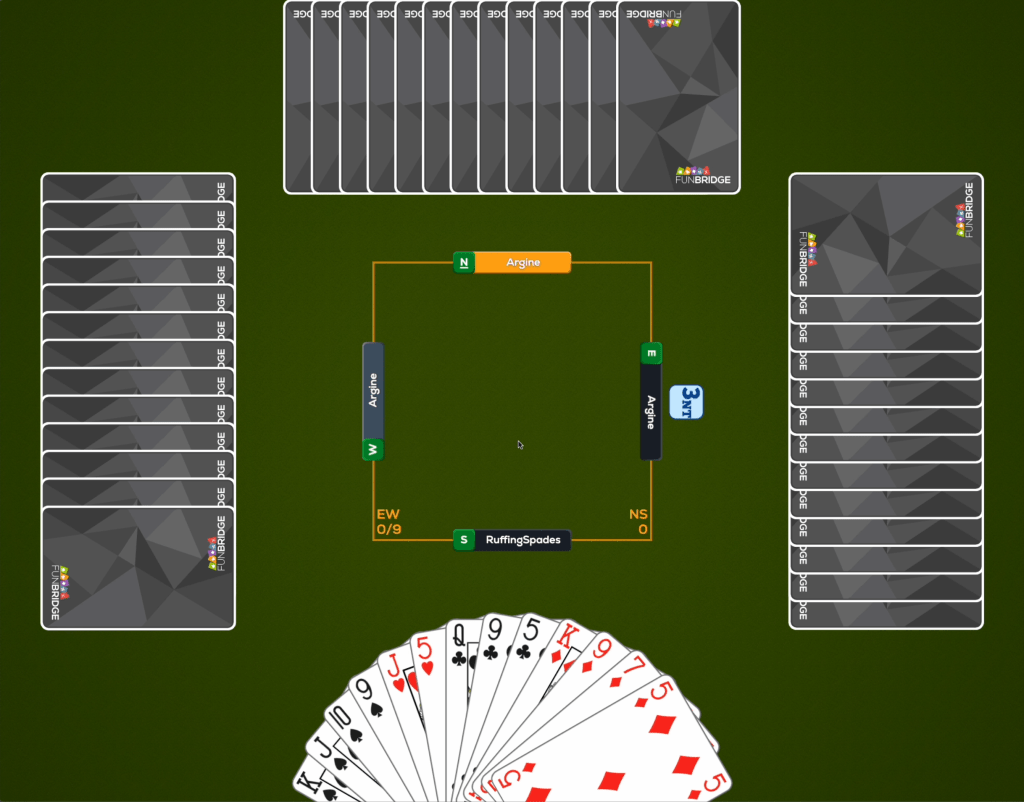

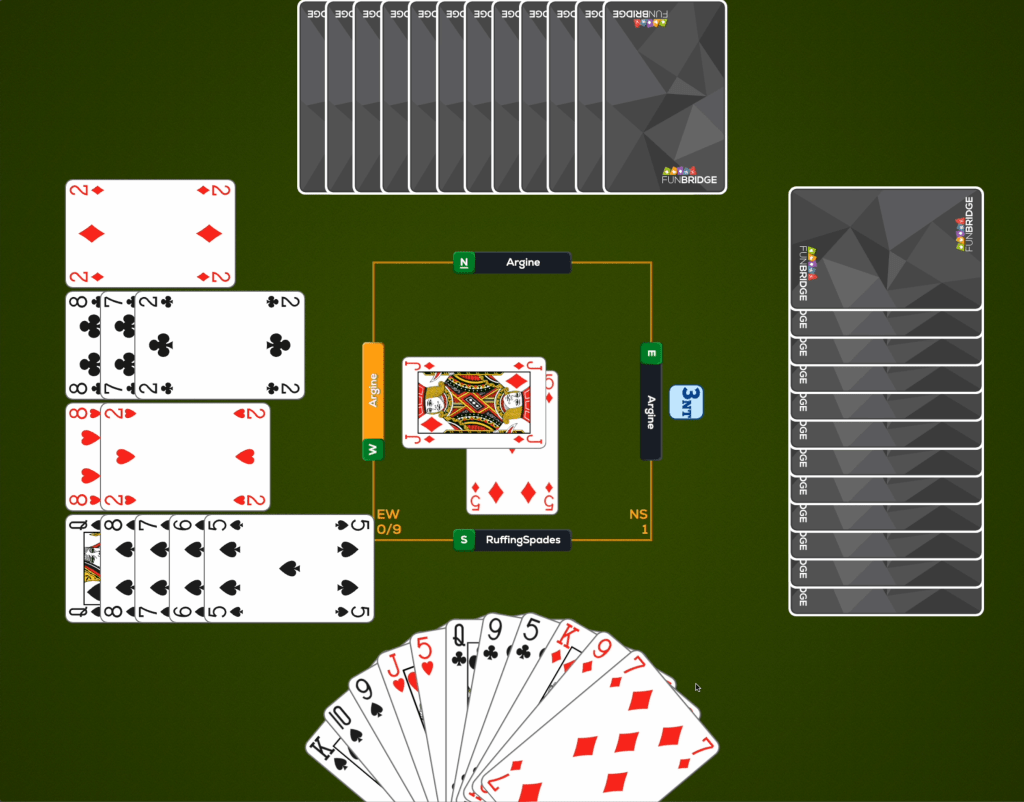

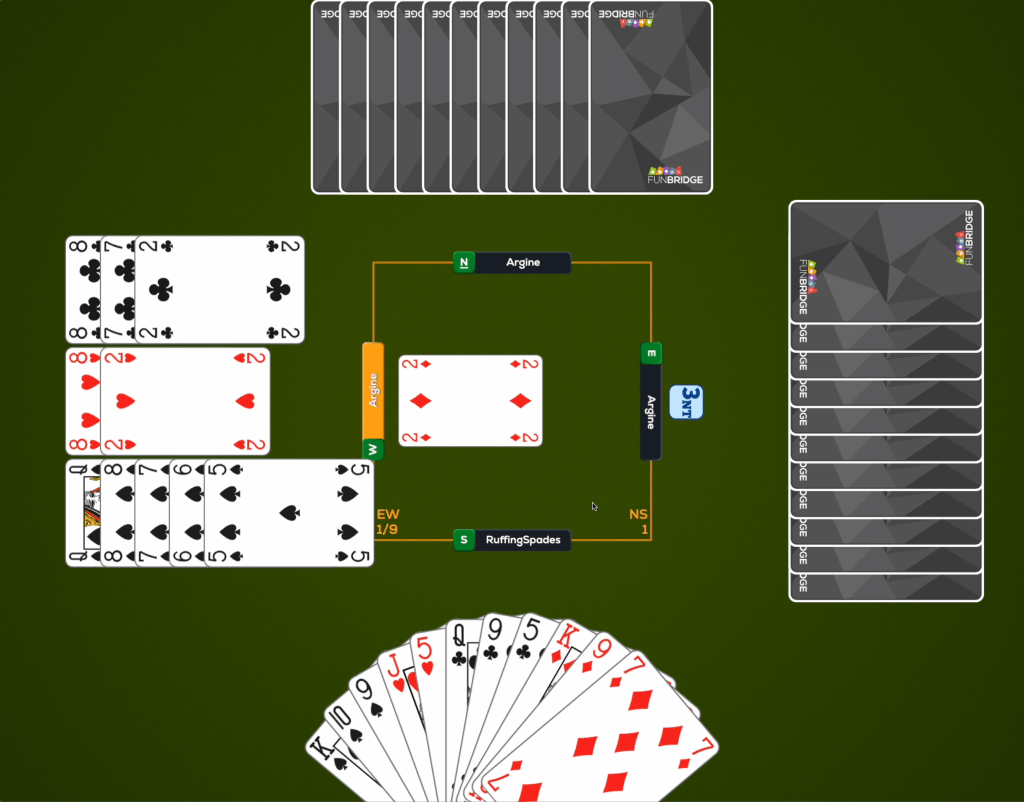

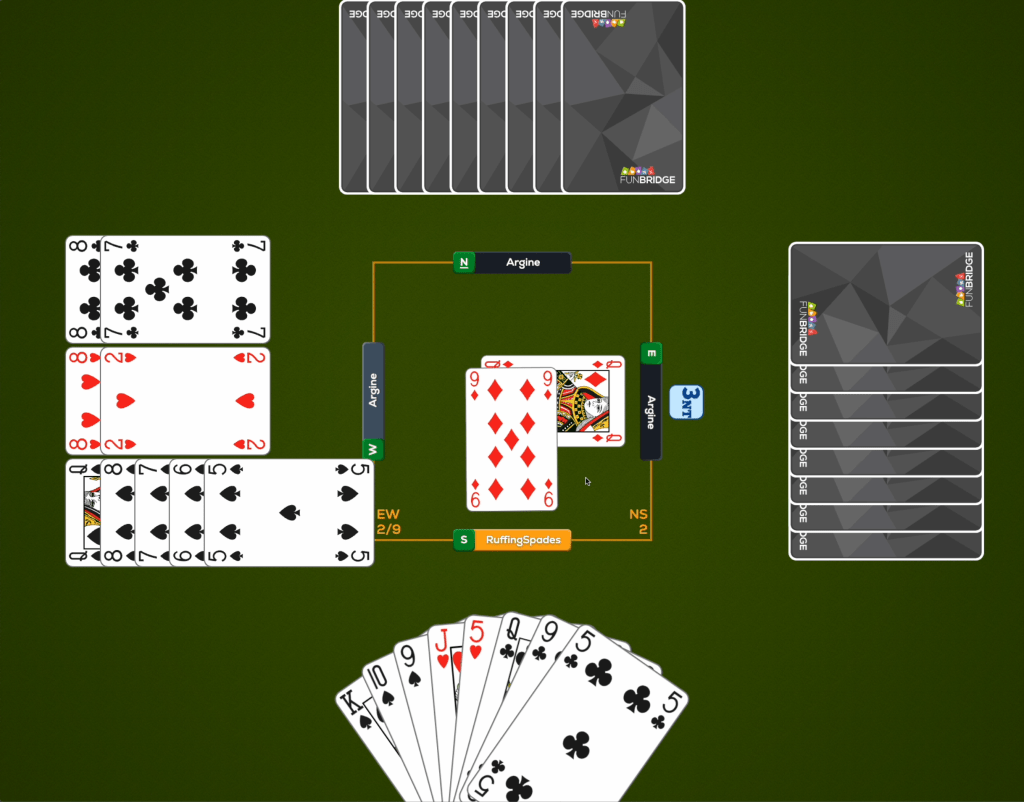

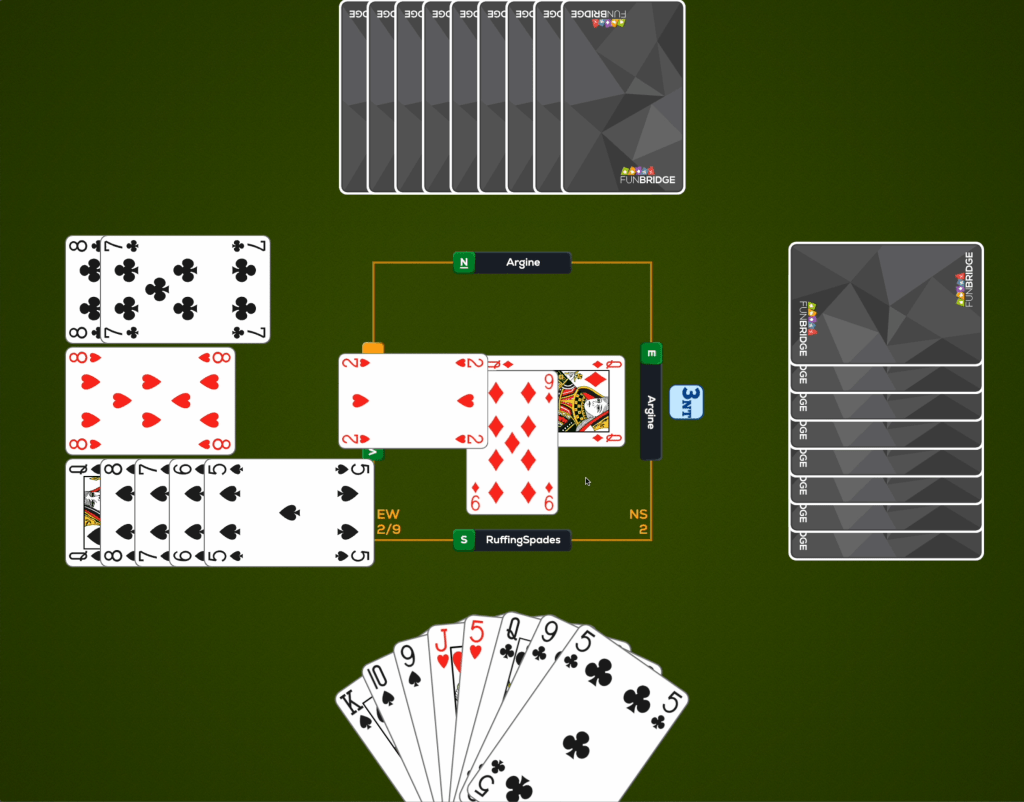

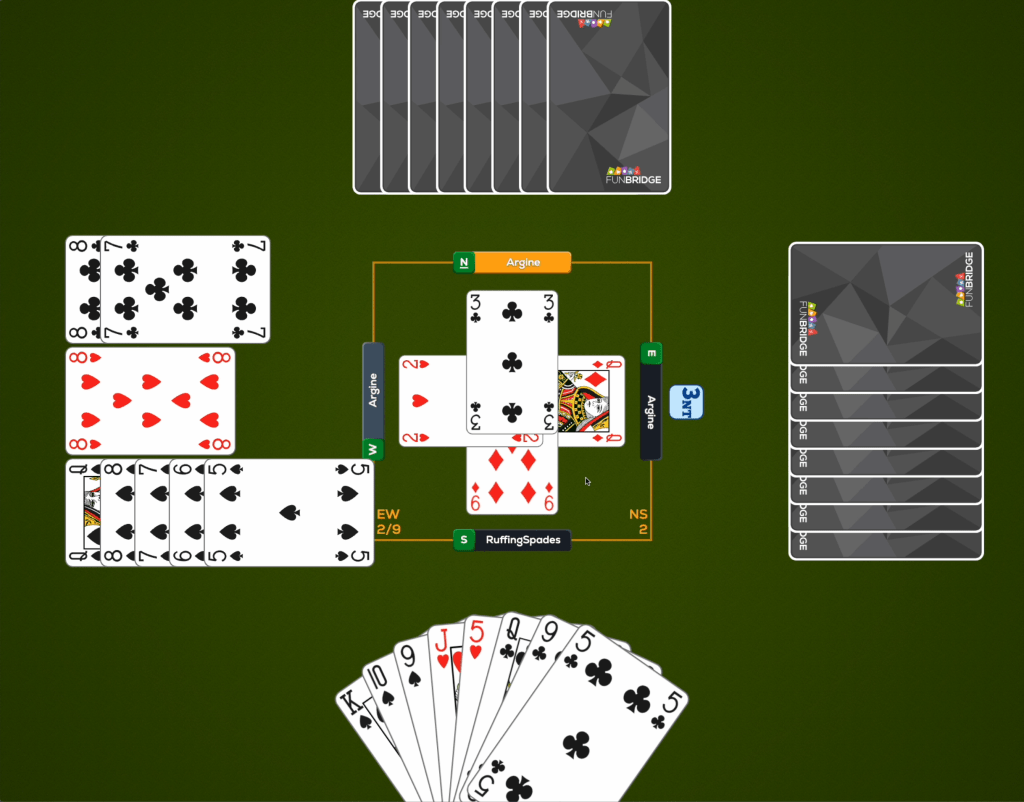

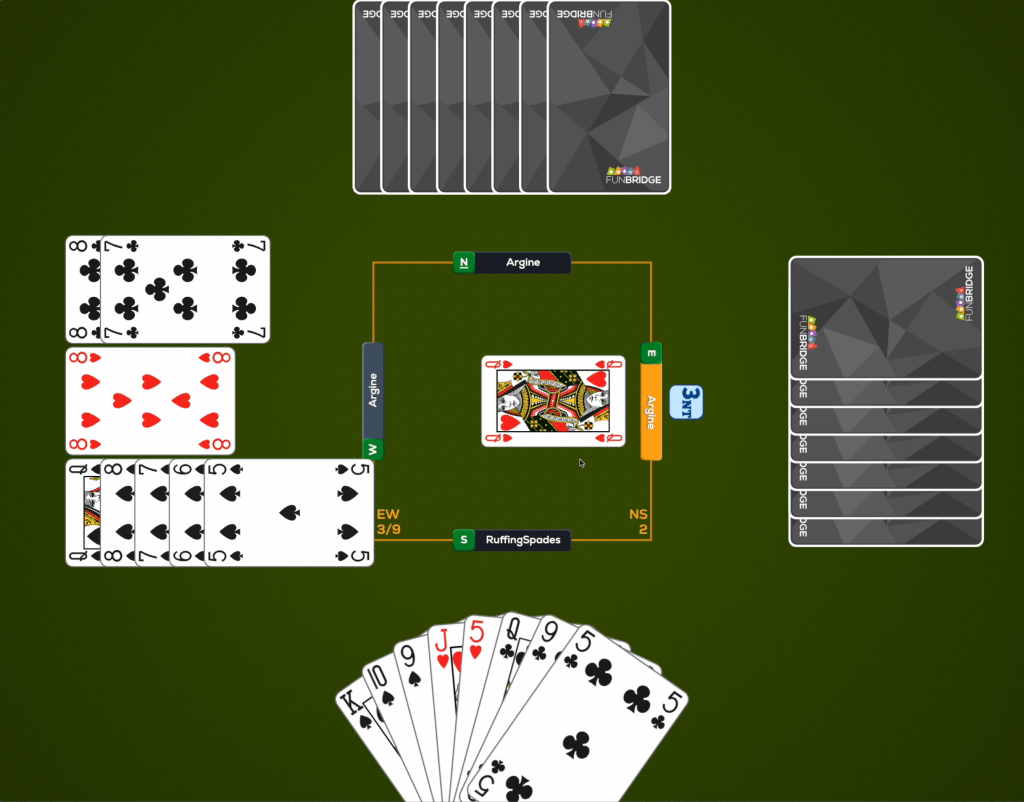

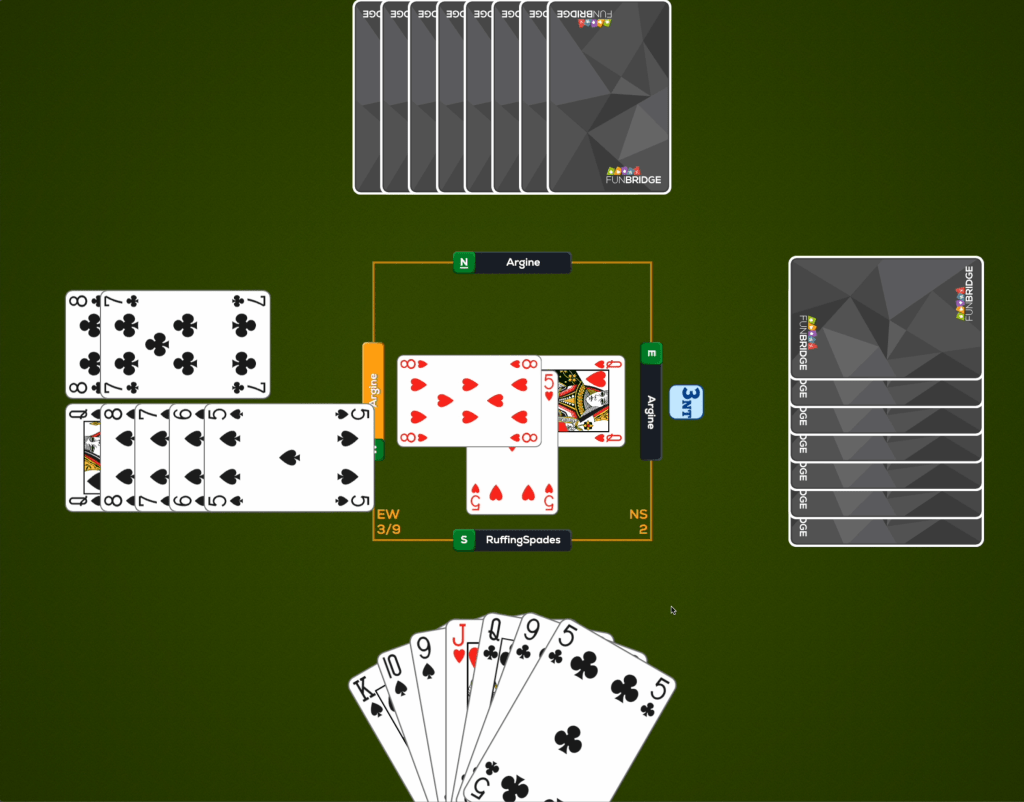

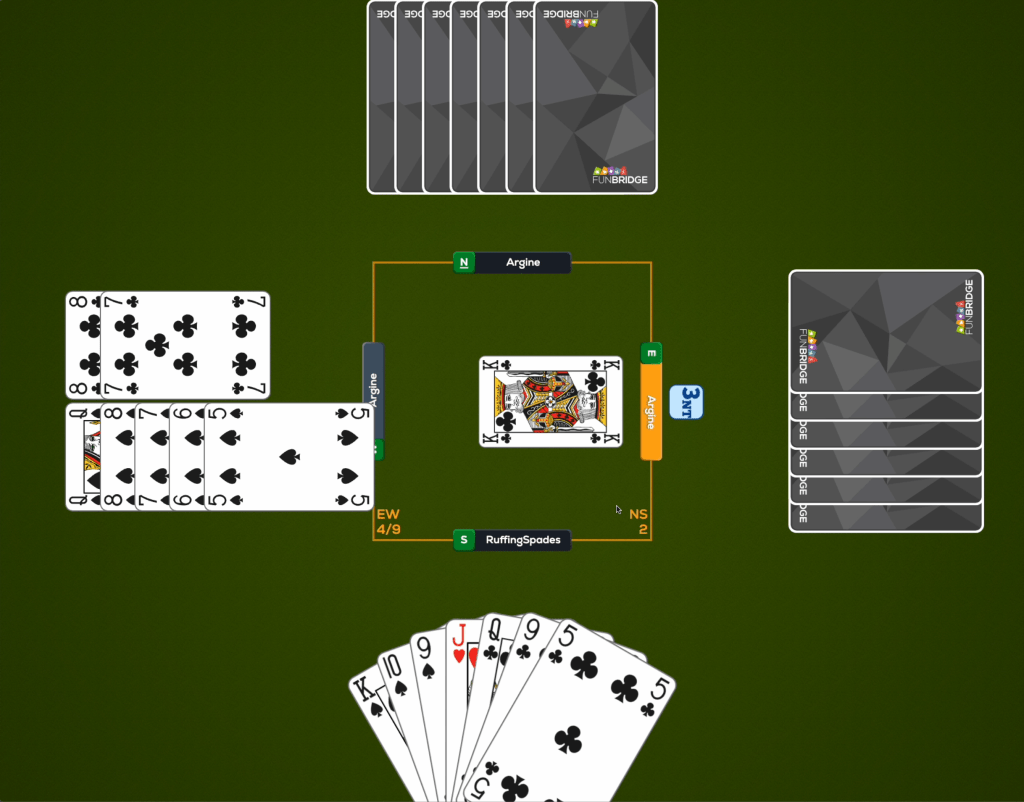

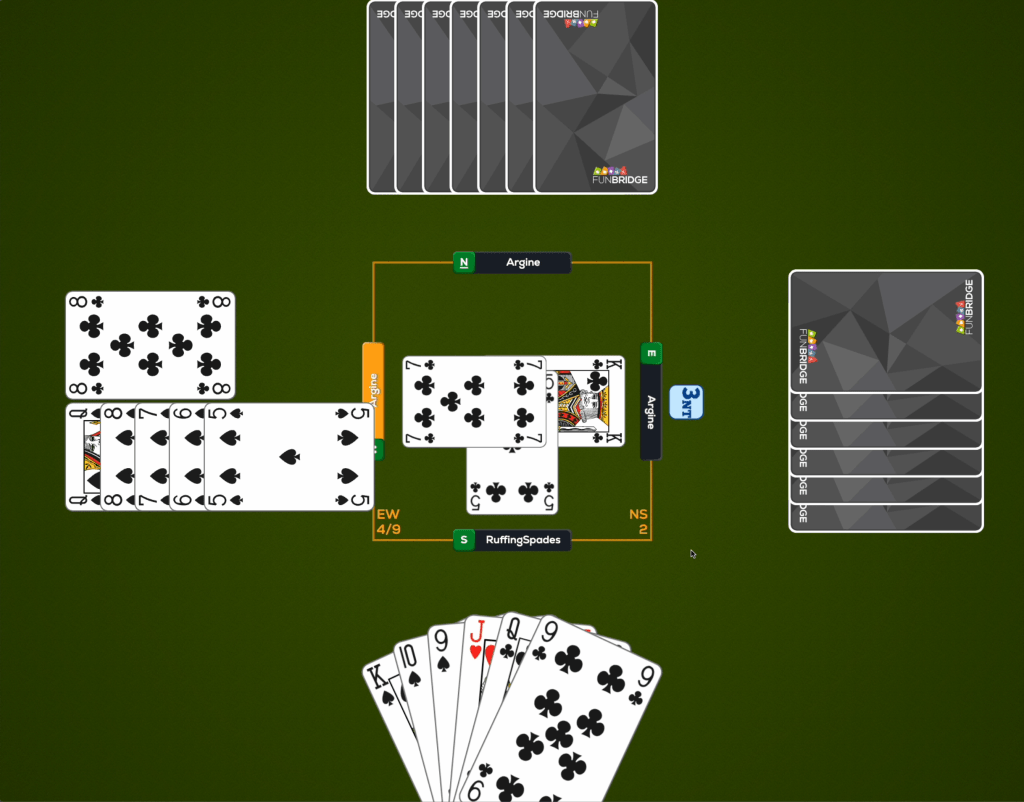

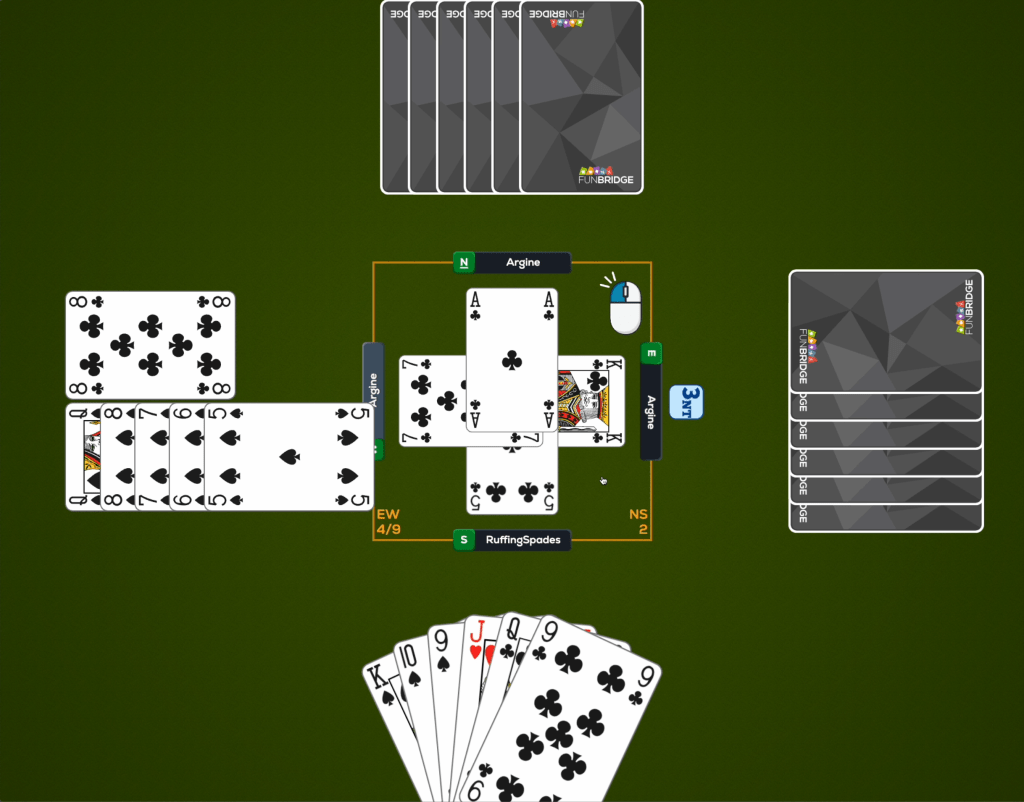

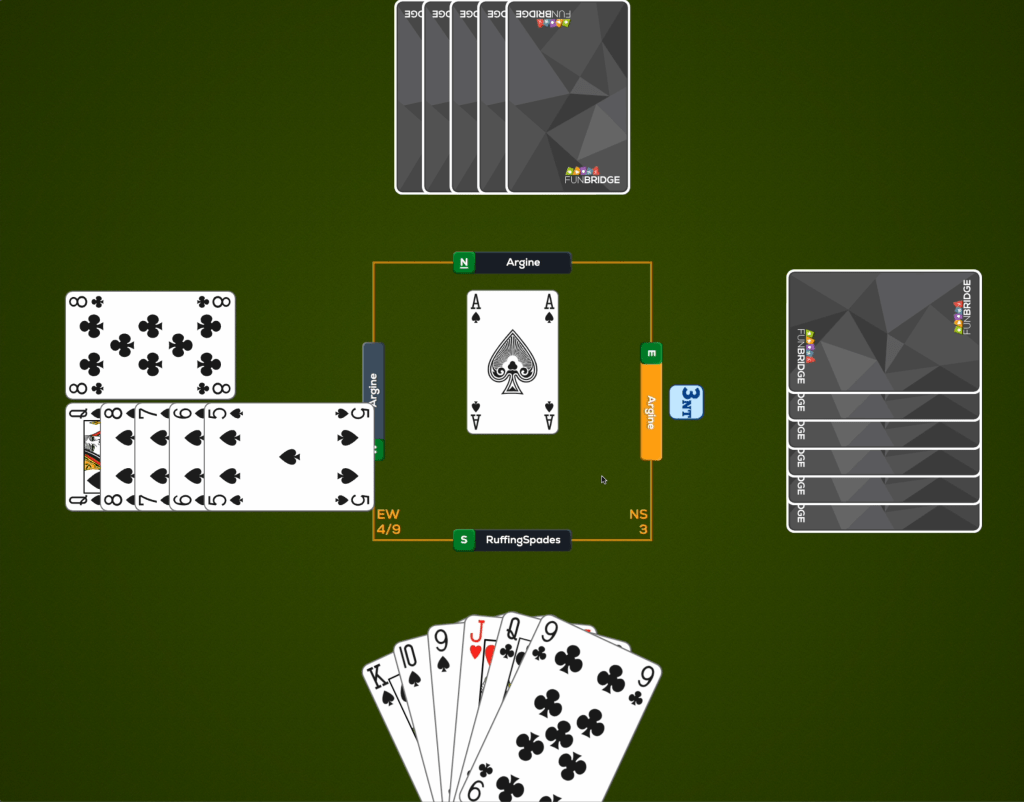

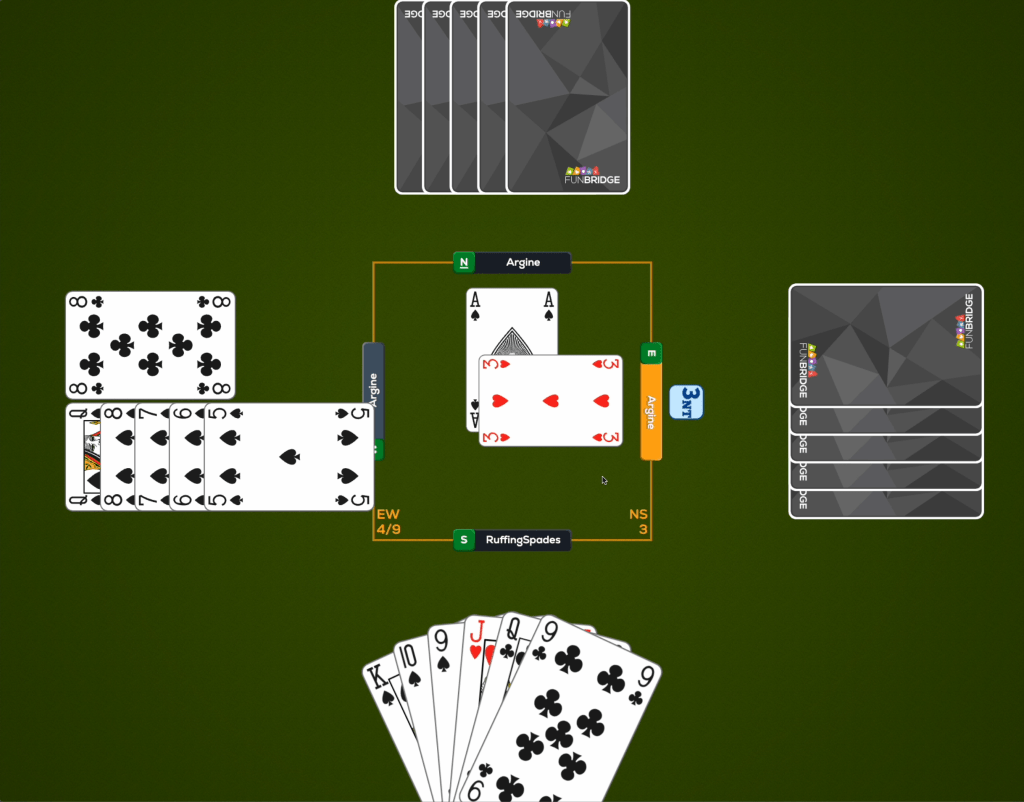

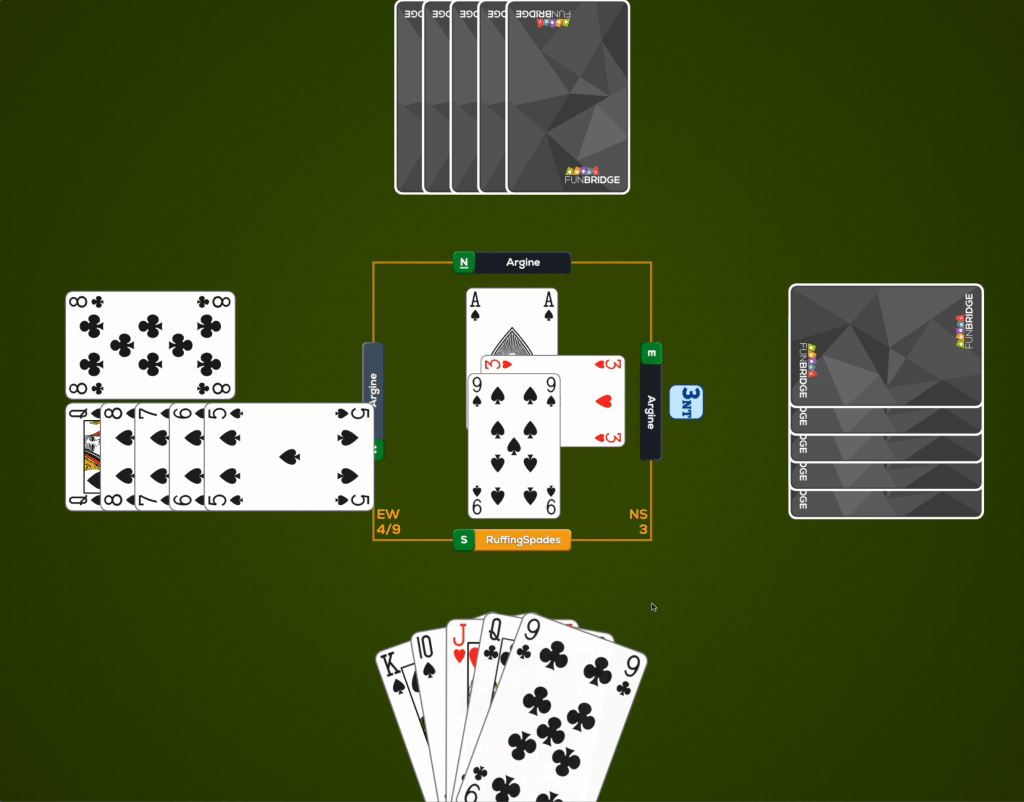

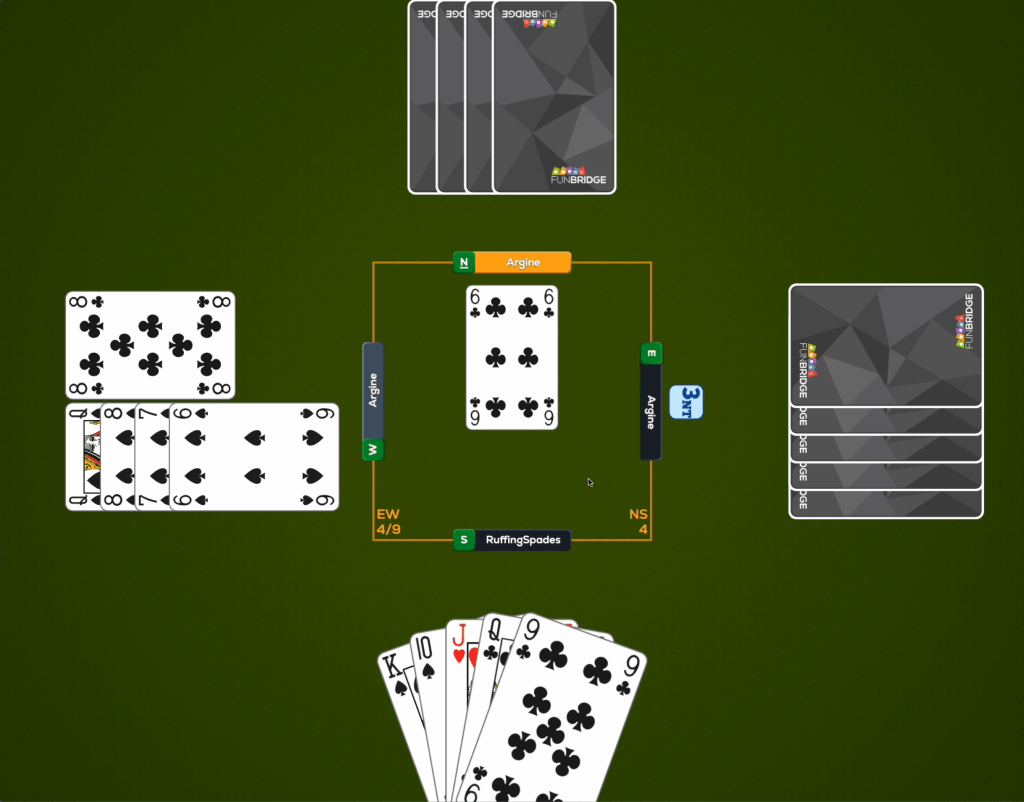

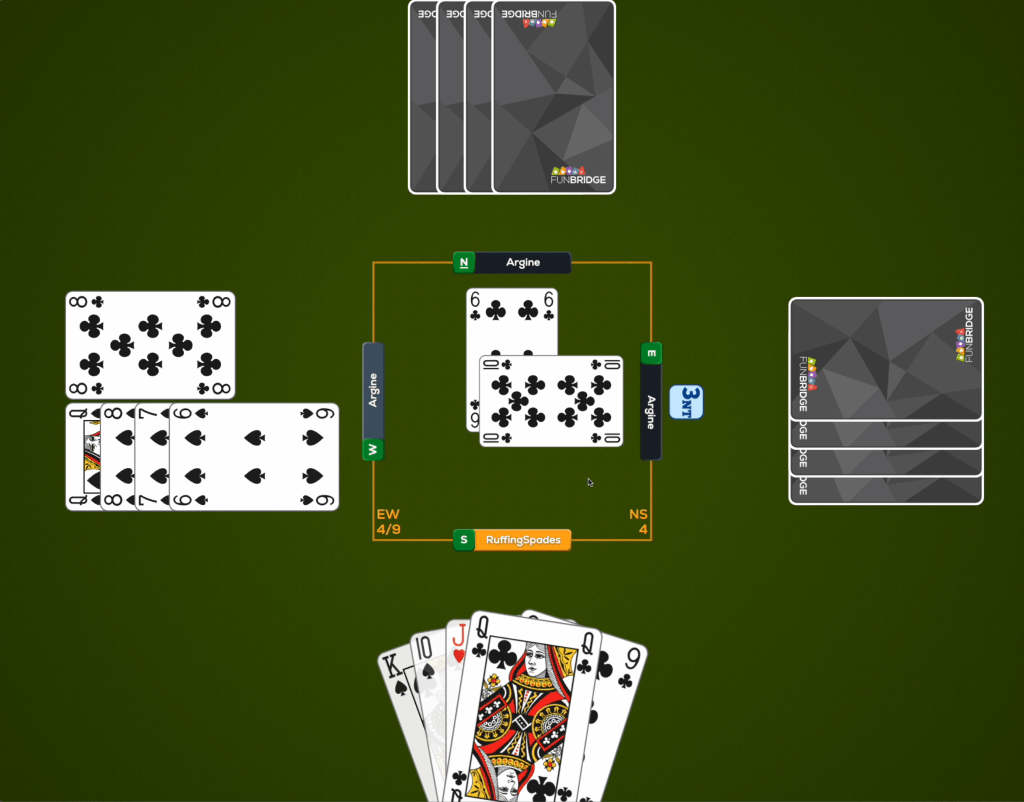

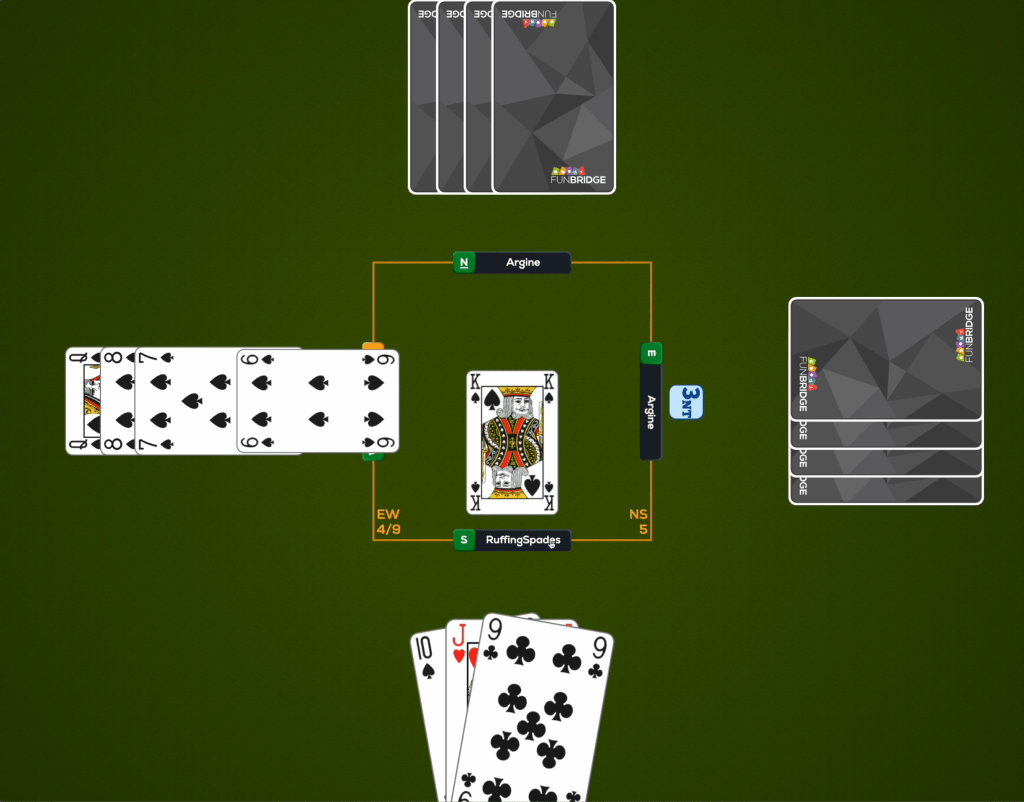

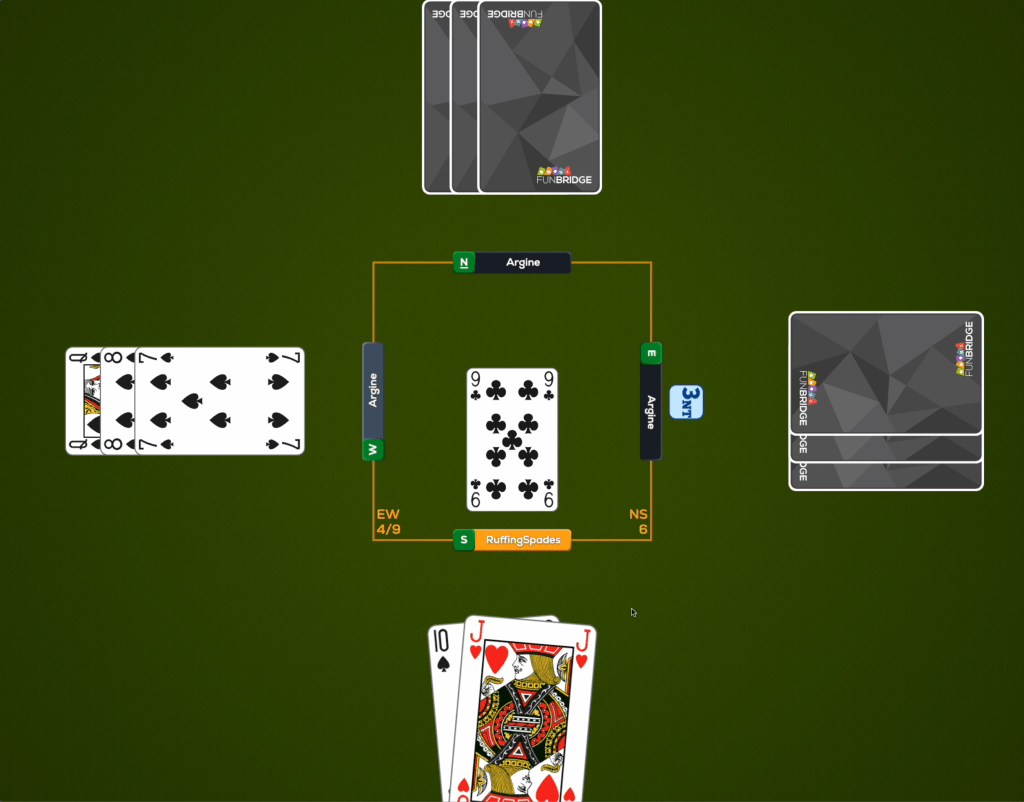

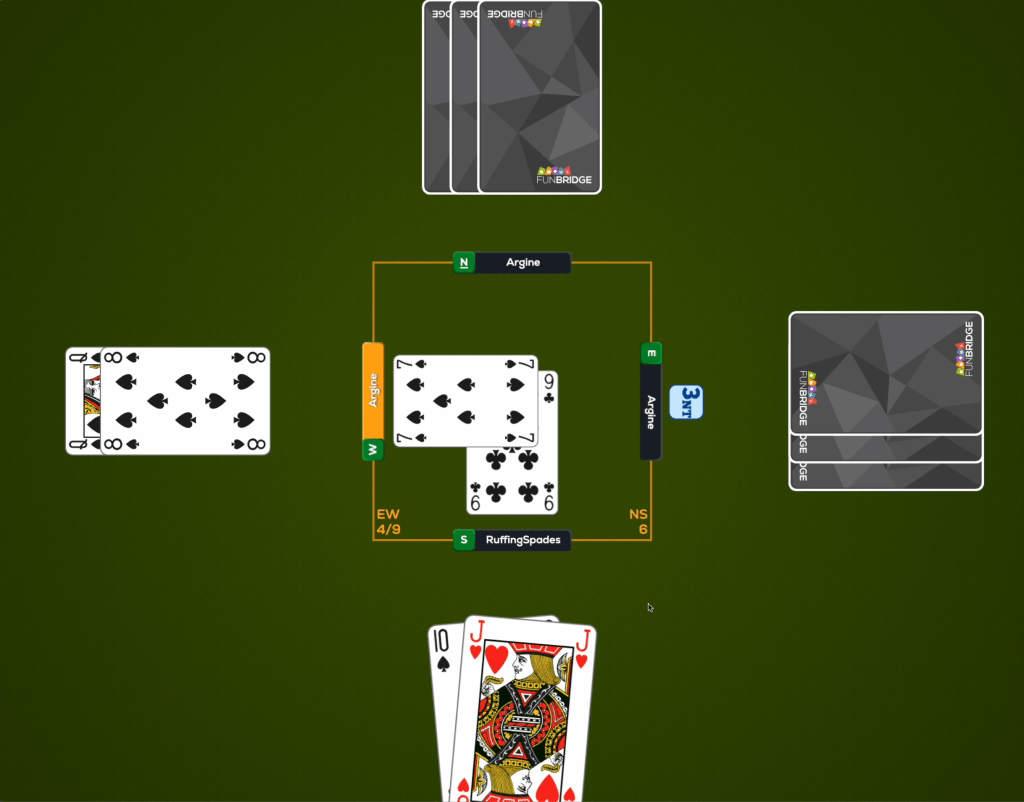

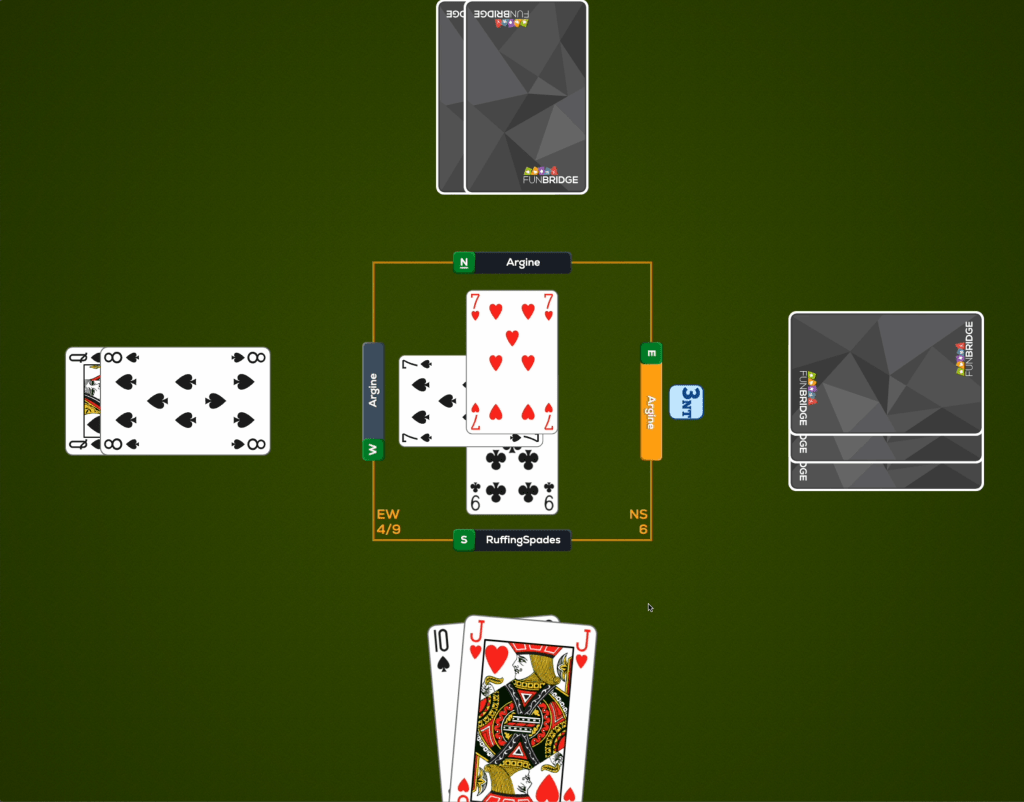

The first trick is a little different than the rest. The player to the left of the declarer (declarer being the winner of the bidding phase) opens the first trick. Then, when it’s turn for the declarer’s partner to play, he lays all his cards on the table, visible to all players… and that’s where his contribution ends. Until the end of the deal it’s the declarer who will choose which card to play from the dummy. Even though it’s the declarer who chooses the card to be played for the dummy, the card is played on the dummy’s turn. Let’s look at some examples.

Example 1. N is the declarer (so S is the dummy). It’s the 3rd trick of the deal. Last trick was taken by E. So this trick is opened by E and he plays K♥. N chooses 3♥ from the dummy. Then W plays 2♥ and, lastly, N plays A♥. This trick is taken by N.

Example 2. E is the declarer (therefore W is the dummy). The trump suit is hearts. It’s the first trick, so S will open the first trick. S plays Q♠. W puts his cards down on the table and E selects A♠ from the dummy. N plays 2♥ (and smirks). Then E plays 7♥ (and smirks even wider than N). This trick is won by E, since he played the highest trump. From this trick, we can also learn that neither N nor E have any hearts in their hands, since if they had any they would have to play them.

Example 3. N is the declarer (so S is the dummy). The trump suit is spades. It’s the 11th trick of the deal. The last trick was won by the dummy. N chooses the card to play from the dummy – 7♥. Then W plays 2♦, N plays 4♦ and E plays 3♥. There were no trumps played so S, the dummy, takes the trick.

As a courtesy, the dummy usually stays at the table and helps the declarer physically play the cards as it’s sometimes hard to reach across the table. However, the dummy is only supposed to play what the declarer loudly announces should be played. If you play online, the dummy will not be able to click on anything – their presence at the table diminishes to more or less welcome chit-chat until the end of the deal.

Pro tip: Note the consequences of laying the dummy’s cards on the table: the declarer knows exactly what cards the opponents have (although he doesn’t know which opponent has which card).

Key points from this section

- Card play begins after the contract has been established.

- The contract establishes the trump suit (or the fact that there is none) and the number of tricks the attacking team is promising to win.

- The goal of the attackers is to take the promised number of tricks or more, the defenders try to stop that from happening.

- The declarer is the attacker who won the bidding.

- The person to the left of the declarer opens the first trick (leads).

- After the first card of the deal is played, declarer’s partner lays their cards on the table as a dummy. The declarer is the one selecting cards to play from the cards on the table.

- The players have to play a card matching the suit of the first card in the trick, unless they don’t have any. In such a case they can play any card.

- When opening a trick, a player can play any card.

- When all four cards in the trick have been played, the winner is the player who played the highest card matching the suit of the first card in the trick, unless any trumps were played – then the highest trump takes the trick.

- The next trick is opened by the player who won the last trick.

- The players keep playing until 13 tricks have been played (so until they have no cards left).

Bidding

Now that we know what tricks and the trump suit are, let’s talk about the bidding (or auction).

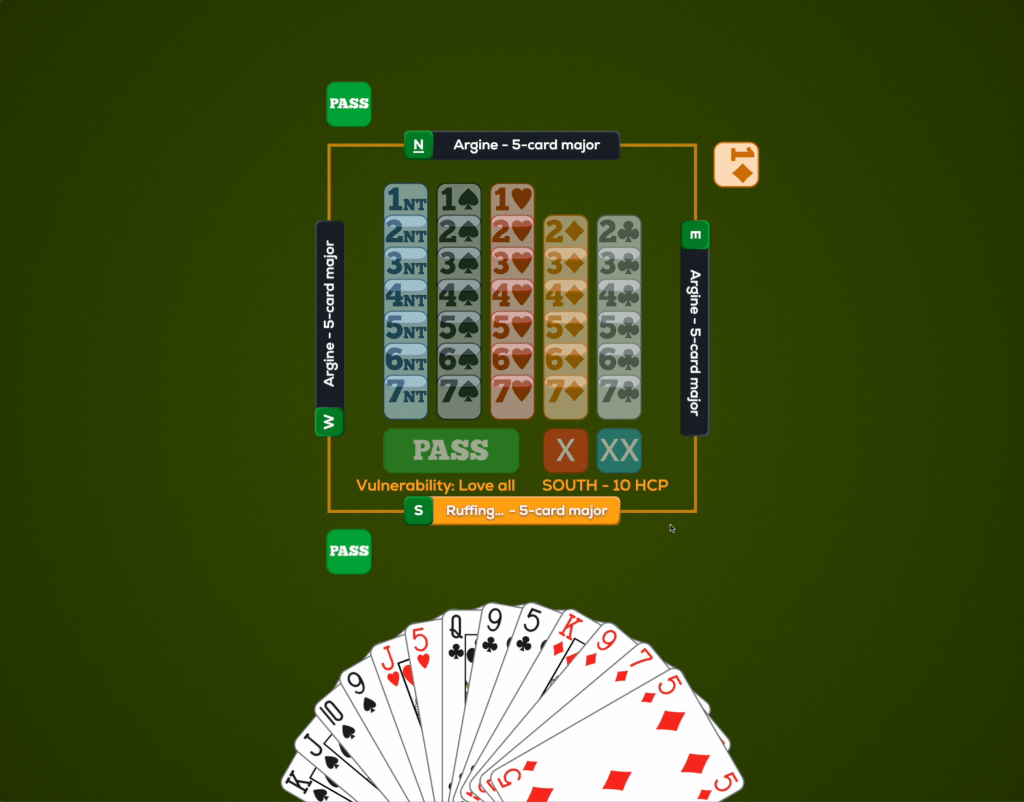

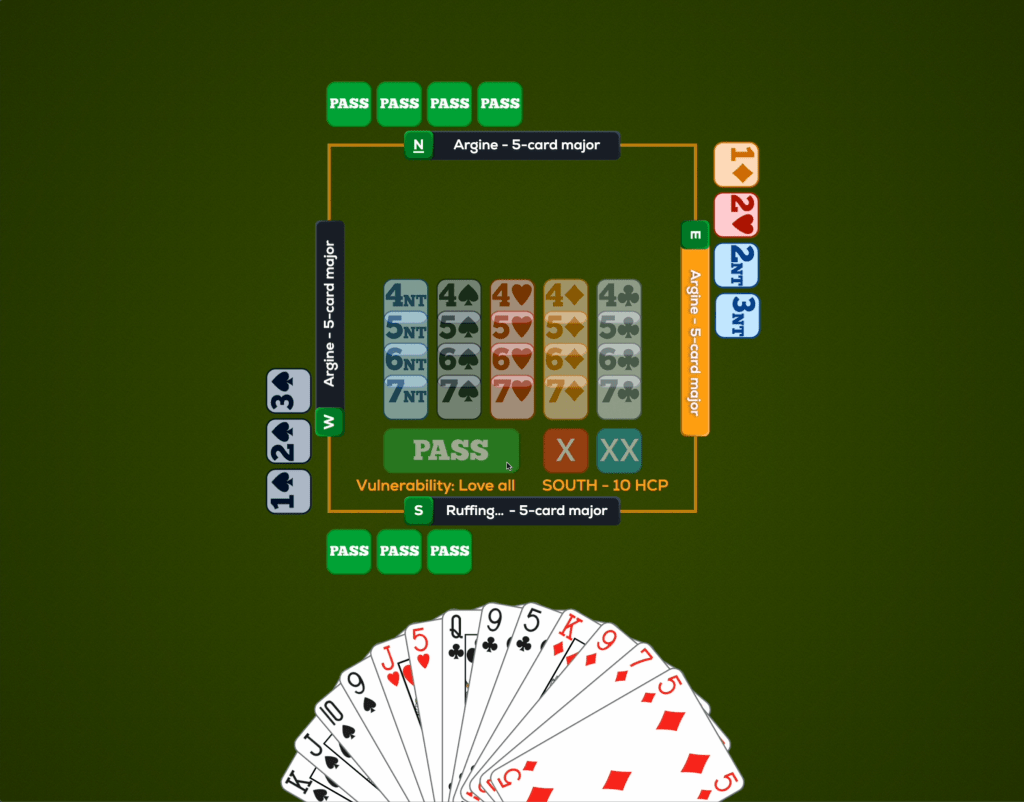

Do you remember that I called one person a dealer? This guy will open the bidding. And then, going in the clockwise order, the players will bid on how many tricks their team will take during the card play. I consider it easiest explained through basic auction common sense and showing a bidding box.

By common sense I mean – in an auction it only makes sense to bid more than the previous bidder has. It doesn’t make sense for my opponent to bid 10 tricks and then for me to bid 8, does it?

But you might also recall that I said a contract holds not only the information on the number of tricks but also on the trump suit. Each of our bids will mean: we declare to take X tricks, if Y is the trump suit. And now we can go and take a look at the bidding box.

The bidding box is a bridge accessory – useful but not indispensable. When players bid with a bidding box they put cards from the box on the table. Don’t worry about not owning one ready for your first games of bridge. It’s perfectly fine to simply announce your bids out loud and hope your friends remember who bid what. On the upside – the players get to exercise their memory.

But going back to the picture of the bidding box, I want you to focus on all the cards in the back panel of the box – the ones with numbers and suits. These and the pass card are the cards we’ll be interested in this lesson. Each of these cards is a possible bid. Each has a number – signifying the trick count, and a suit – signifying the trump suit we want to play. I’m guessing two oddities caught your attention already: why do the numbers go from 1 to 7 if there are 13 tricks in a deal and what is that NT thing?

About the numbers on the bids, add 6 to each and this is how many tricks the bid is promising. It doesn’t make sense to bid that your team will take 6 or less tricks – such a bid would mean you’re bidding the opponents will actually take more tricks. Therefore the reasonable bids start at 7 tricks. I imagine someone somewhere thought it was redundant to deal with numbers from 7 to 13 and brought it down to 1 to 7 – efficiency.

About the NT bids, NT simply stands for ‘no trump’. If a no trump contract is played, it means there is no trump suit. It’s impossible to win the trick if you don’t play a card matching the suit of the first card in the trick.

Now that we have these oddities handled, let’s go back to the rest of the box. You can see that the suits are in a set order: club, diamond, heart, spade and NT. This order is always the same and it dictates which bids are considered higher at the same level of tricks. A bid of 3♥ is higher than a bid of 3♦ (but 3♦ is higher than 2♥). Therefore if someone bid 3♦ before, you can go ahead and bid 3♥. However, if 3♥ was just bid, you cannot bid 3♦ anymore.

When a player’s turn to bid comes they can do* two things: bid or pass. If they bid, they have to bid higher than the last non-pass bid. If a player doesn’t have faith in his hand (the cards he was dealt) or is happy with what his team has bid – they can simply pass.

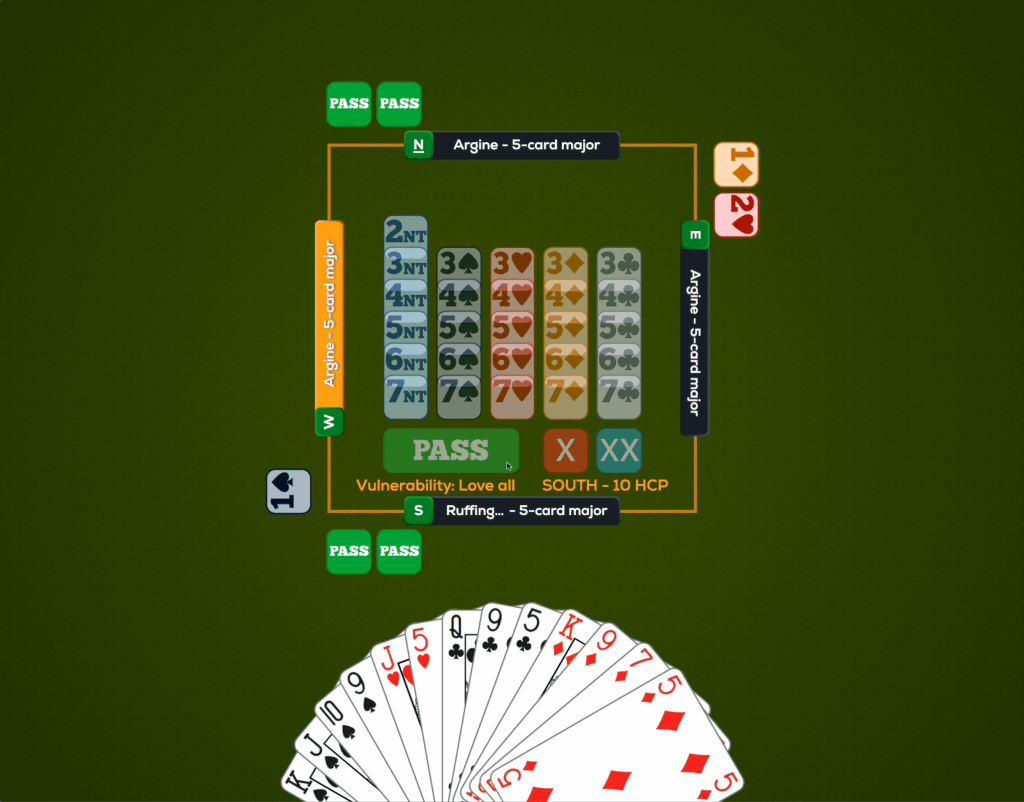

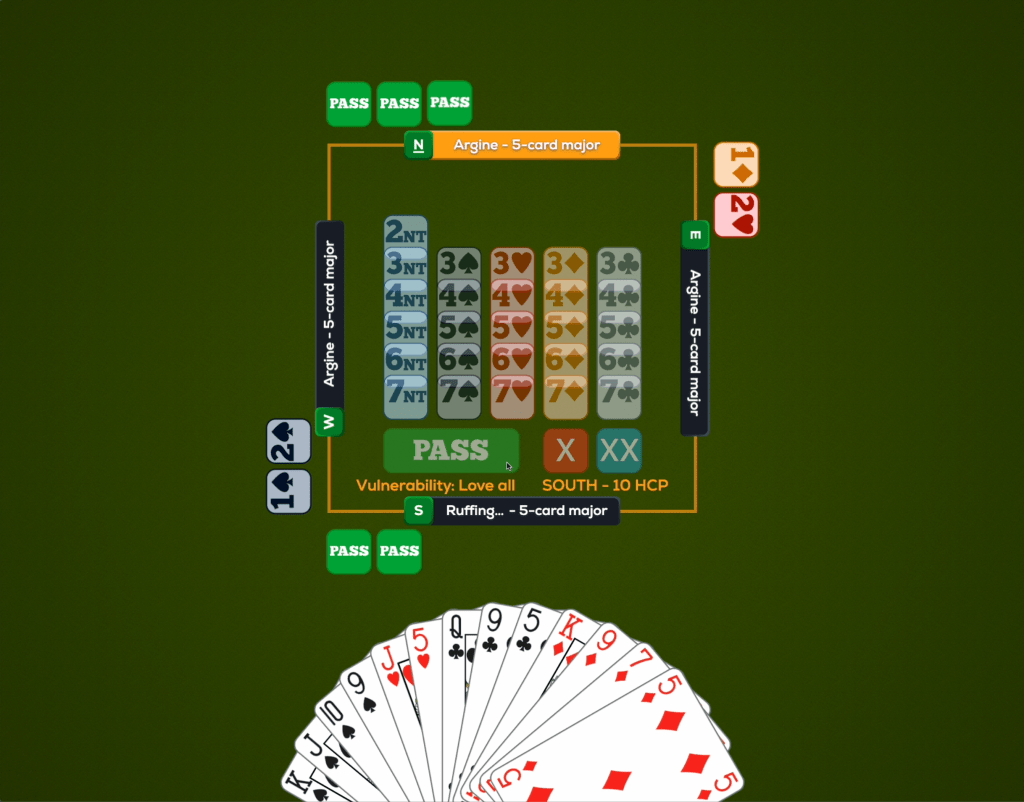

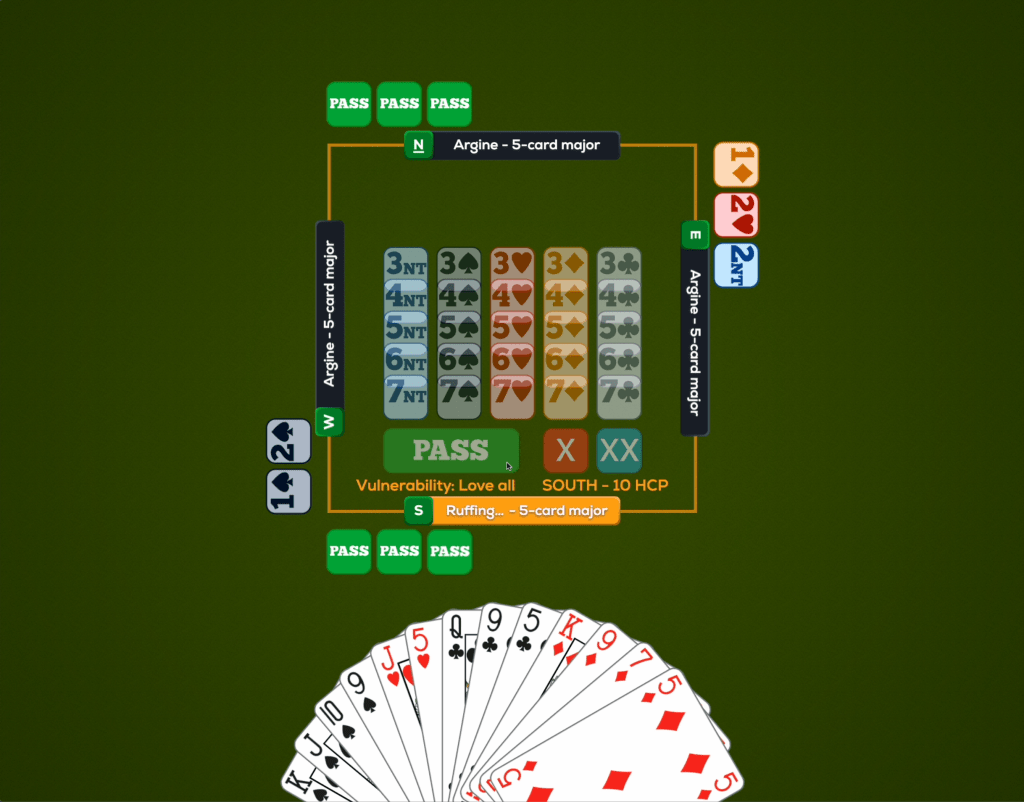

The bidding ends after three bids in a row are a pass. The last bid is the winning bid and the team who won the bidding will be the attackers in this deal, while their opponents will be the defenders. Who’s the declarer? Contrary to what might be the most intuitive idea, it’s not the player who bid last. It’s the attacker who bid the suit of the final contract first.

Remember that even though we bid on how many tricks we’ll take as a team, each player has their turn to bid and the teammates can one-up each other. It’s perfectly legal and reasonable for the bidding to go as follows.

Example 4. N, as the dealer, opens the bidding with 1♥, E passes, S bids 2♥, W passes, N passes, E passes. In this the contract is 2♥, and the declarer is N, since he’s the one who first bid hearts. We say that N plays the contract of 2♥.

Pro tip: An important and integral part of bidding is reading other players’ bids – especially your partner’s. If you have a nice hand and see your partner bidding aggressively – sky’s the limit. It’s also a positive sign if you see your partner bidding a suit that you have strong cards in.

Fun fact: What if everyone at the table dislikes their hand? It’s a possible scenario that none of the players wants to bid and they pass. In such a case, when nothing but passes are bid – not 3 passes, but 4 conclude the bidding. If the bidding consists of four passes, the deal is considered passed out and a neutral score is given. It’s not a common occurrence but not something unheard of either.

Example 5. N, as the dealer, opens the bidding and passes. E passes and S passes. As mentioned before – in the case of only passes having been bid – three passes don’t conclude the bidding. W bids 1NT. N bids 2♣. E passes, S passes and W passes. The bidding is concluded and N plays 2♣.

And now we’re back in the play stage. I imagine some things about the play make more sense after learning about the bidding, just how some explanations about the bidding require some understanding of the play.

Key points from this section

- The dealer starts the bidding. After every deal the person to the left of the dealer becomes the new dealer.

- The players place their bids going in the clockwise direction.

- You can always pass. You can only bid higher than the last non-pass bid. A bid is considered higher if it promises more tricks (any suit/NT) or the same or higher number of tricks but with a higher trump suit (with NT being the highest ‘suit’). The order of suits is from lowest to highest: clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades and NT.

- The bidding ends after 3 passes were played in a row, unless only passes were bid – then 4 passes are required to conclude the auction.

- The last bid is the contract. The team of the player who bid the contract are the attackers and their opponents are the defenders.

- The attacker who first bid the suit (or NT in case of NT) of the contract is the declarer.

The goal

And now back to the elephant in the room: who wins? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Every contract has its point value. If you win the contract you get points, adjusted for every extra trick over the contract you took. If you lose – your opponents get points. If you really want to know the scores, you can check out the scoring table here. However, I don’t think it’s productive to look at it yet and I won’t explain how to read the table for now. I just want you to focus on two things:

- getting the contract as high as possible,

- winning the contract.

Note the ‘as high as possible’ bit. The contracts that are winnable will depend on your luck in a deal. That’s why when we play tournaments, the same deal is played on multiple tables – only then can you compare the scores fairly.

As you go through further lessons, and get experience playing, you’ll start understanding what potential your and your partner’s hands have. And then you will understand that it’s a game of making the most with the hand you were given. In this way, bridge is just like life.

Sample deal

Pro tip: At any point in the card play the declarer can show his cards to the defenders and claim. In the claim he will declare how many tricks he’ll take. It serves only as a way to shorten the time the card play takes, when it’s obvious. An example is, if the opponents have no trumps left and the remaining cards in the declarer’s hand are trumps. In this case there is no other possible result but that the attackers will take the remaining tricks. It is possible however that the declarer makes a mistake. If you defend, you don’t have to accept the claim. You can reject it. Then, the declarer’s cards remain visible for all and the play continues as if nothing happened.

Practice

Now, you’re ready for your first bridge deals.

If you’re on your own or with one friend, jump on BBO. Don’t be shy and don’t worry you’re getting your butt whooped. Just do your best and see for yourself how the game is played. If you have a friend you can use BBO to play as a pair.

If there’s four of you, you’re in luck. You’re ready to play your first deals.

Don’t worry if you feel lost, confused or overwhelmed. That’s totally expected and will get better with just a few more lessons. Get the feel for the game – when it’s a good idea to play a high card, when it’s a good idea to bid high. It’ll be a great start to your bridge journey.

Something’s unclear? Having questions? Contact me!

Leave a comment